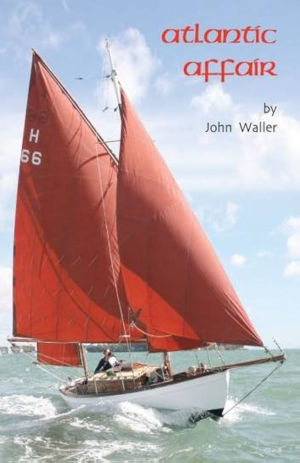

Atlantic Affair

Atlantic Affair consists of three parts. Part One is a description of Otway Waller’s single-handed voyage made in his 26ft yawl in 1930 following the route of his friend and gun-runner Conor O’Brien’s circumnavigation, in which he demonstrated the value of the self-steering system he invented, the first to enable a yacht to run unattended before the wind. It introduces the reader to a brave man, whose journey would fulfill many landlubber dreams today. It also explains the final and shocking cause of the break-up of Otway’s marriage.

At the end of Part One, Otway, who is seriously ill with a divorce pending, decides to return to Ireland to face his wife Muriel and his son Peter. This is dealt with in Part Three.

To understand these three characters, we need to go back to Otway’s and Muriel’s courting and Peter’s childhood. Who better to tell this story than Peter? He wrote an autobiographical manuscript, the second half of which became Irish Flames - Peter Waller’s true story of the arrival of the Black and Tans. Part Two of Atlantic Affair incorporates even more of Peter’s manuscript.

The final third of the book follows directly on from Part One. In 1930 Otway is in the Canary Islands suffering from Canary Fever. He decides to postpone his voyage on the Imogen and return to Ireland to face a divorce, the split in his family and community, the torching of his house and being forced out of Ireland by a UK monopoly supplier.

Peter Fernie, the Editor of the Irish Cruising Club, reviewed Atlantic Affair for the Autumn 2014 edition of their newsletter. He says: "This is a family memoir recounting the life of a charismatic ICC member Capt. Otway Waller, whose tumultuous life straddled a chaotic time, which included the Irish war of independence and the first and second world wars. Of interest to sailors is his single handed crossing of the Bay of Biscay, and then on to the Canaries.”

PART ONE - THE VOYAGE OF THE IMOGEN

From journey's start

To journey's end

Appendix 1 - Running sails

Appendix 2 - The Log of the Imogen

Appendix 3 - The history of the Imogen

PART TWO - THE STORMS GATHER

Peter is born

Home to Invernisk

Peace at last, but not for long

The Regatta Race

The arrival of the Black and Tans

PART THREE - A SECOND MARRIAGE

A new journey starts

Catch me if you can!

An Irish welcome

To England and the war

To a sportsman’s end

Epilogue

Appendix 4 - A letter from Afghanistan 1842

Appendix 5 - Extracts from the Court Case

Appendix 6 - A solution to potato blight

“A voyage single-handed makes a tremendous demand upon the courage and stamina of any man. Capt. Otway Waller will do it if anyone can. He is a fearless fellow.”

The Irish Times June 14, 1930

June 27, 1930

Bad arthritis in my back last 2 days, can only lie on my back, if it gets any worse I’m through.

From Otway Waller's log of the Imogen, 1930

Otway Waller lay wedged on his back on the floor of the cabin with the mattresses from the settees holding him steady. Since leaving Ireland twelve days before, mountainous seas had treated his little yacht as a cork in a turbulent stream. Wherever the waves came from, he could at least sleep in a stable position.

Lying there in agony as his arthritis – perhaps the result of the wear and tear of a maniacal sporting life – forced him to question his future journey. He asked himself why he was in the Bay of Biscay, still 126 miles from the nearest point of Spain and less than half way to Madeira, his initial destination and possibly now not to be achieved. He managed a smile as he remembered that bad luck came in threes: a broken marriage, then broken rigging and now a broken back. He smiled again as he thought how the Imogen, his 6-ton, 26-foot yawl had ridden the gale that had broken her rigging. Years of sailing off the west coast of Ireland had toughened both boat and master.

If Otway’s journey to Vigo had been hell with head winds much of the way, his voyage on to Madeira was heaven. From the moment he left Vigo Bay, the NE Trades, almost ideal with Funchal 710 miles to the WSW, bowled him along like a steamer. For three consecutive days, he covered over 100 miles.

On his seventh day out of Vigo, after he had had nearly a fortnight of perfect sunny weather, the clouds came in and the sky was overcast, indicating land was not too far away. The low-lying island of Porto Santo with its spectacular six-mile sandy beach stood in his path 20 miles before Funchal, which was barely a day’s sailing away.

Without the sun he could not calculate the longitude and determine his exact position, so he left his sextant and stopwatch all ready outside. Suddenly the sun appeared for less than half a minute and he was able to take a reading, just 15 miles from where he had expected. His navigation was self-taught. He had practised sextant work with an artificial horizon composed of lubricating oil in a tea tray set on the lawn in front of his house.

* * * * *

Now seriously debilitated, he rested up for a couple of days [in Santa Cruz, Tenerife] and was unable to travel inland. The reporter of the local paper, La Tarde, came on board to interview him. He wrote in the July 31st edition:

“On the 28th inst. the Irish yacht Imogen of four tons anchored in our harbour. Yesterday, at an early hour, she departed for the neighbouring island.

To this new and gallant solitary navigator, we wish much luck in the risky enterprise, which he undertakes with so much enthusiasm.”

Still unaware of the cause of his illness, he left Santa Cruz on Wednesday July 30th at 5.30 a.m. For five hours he drove Imogen into a heavy sea and strong wind. Soaked by the heavy rain, he was relieved when the sun came out at 11 so he could change his clothes, have breakfast and then have a good sleep. At 9 p.m. he arrived at Las Palmas, took in the sails outside the harbour and motored in.

Concerned about his health, he decided that he should not sail on but try and get a boat home to Ireland. Imogen lay steady for the first time since the night in Foynes in the mouth of the Shannon on June 15th.

There has been debate over the first yachtsman to use a self-steering system to run before the wind on a long-distance solo voyage. The Frenchman Marin-Marie, who was the painter to the French Ministry of Marine and a single-handed Atlantic sailor, wrote in his book Wind Aloft, Wind Alow:

“I firmly believed at the time in 1933 that I was the first to make the attempt. Later I discovered that Capt. Otway Waller had before me, although his method took an altogether different form.”

An article in the Tatler in 1931 explained Otway’s invention:

“An invention which is of vital interest to sea-going yachtsmen by which a yacht may be made to run indefinitely before the wind with no one at the tiller, has been introduced by an Irish yachtsman, Captain Otway Waller.

“Although most cruiser-type yachts will keep to their course with tillers lashed and will sail unattended when ‘close-hauled’, or with the wind on the beam, it has hitherto been considered almost impossible to make a yacht run before the wind without someone on the tiller.

“When a yacht is running or ‘scudding’ before wind and sea forces are set up – such as the varying pressure in the sails and the tendency of the overtaking seas to throw the hull round – which cause the vessel to yaw and to ‘steer wildly’. This tendency to broach-to needs constant checking one way or the other by the tiller. Hence the virtual impossibility of ‘letting her look after herself’ before a following wind.

Imogen with running sails set

APPENDIX 2 - THE LOG OF THE IMOGEN

June 15, 1930

Left Foynes 8.25am (New Time). Watch 52secs slow.

Bar 30.00ins. Light NE breeze. Nice run down river with tide and very little wind which fell calm & then went to South. Becalmed in a beastly sea off Kerry Head. Ran engine for 2½ hours runs to try & get out from the land.

June 20, 1930

Watch 1 min 27 slow.

Log 8am 220.4.

Position at noon 49°36'N log 240. Course SSE.

11°44'W at 7.30pm. 170 miles SW by S from the Blaskets

Am hove to again as seas are too high to plug into any more till it changes a bit. Nothing but a dead beat all the way to here, these seas are very fine to watch. I would like to see one of them roll down Banagher Street some fair day!

June 25 1930

Well this is the worst yet. Wind gone round to the East and blowing a full gale. Hope the gear will stick it. Mainsail rather large, can't touch anything, blowing far too hard & torrential rain.

Both watches stopped this morning, forgot to wind them and I don't think the wireless is good enough to get the time signal.

Bobstay carried away. Had to rig temporary forestay of running sail halliards.

Must call in at Vigo to get it fixed. Can't set mainsail anymore.

July 14, 1930

Got London (Chelmsford) again at 12 noon. Haven't been able to get it since Thursday (July 10). Wonder was it broken down.

Wind due North, racing along, should make a good run today. Will know at 1pm. Only seen 1 ship since I left the coast, funny no traffic from the Mediterranean. Tiller sheet broke at 5.30am. Lucky I was awake & heard it go. Must fit stronger one. Position at noon 35°30'N, 14°8'W. 107 miles since noon yesterday. This is my best days run so far. Only 228 miles from Funchal.

APPENDIX 3 - THE HISTORY OF THE IMOGEN

Good wine has a long life. The Imogen is still alive at 102 years old. In the end, she made her way half way round the world to Auckland, New Zealand. If a reader of Atlantic Affair would fall in love with her and sail her home, the author would be forever grateful and perhaps Imogen herself would be happy too.

The current owner in Auckland, John Cooper (Tel: +64 9 967 9279 and Mobile: +64 21 488 388), is interested in selling the Imogen and has provided the following history:

April 1997 - Bought by John Cooper and trucked to Dolphin Quay, Emsworth, for restoration.

1997 to 1999 - Restoration work by Tim Gilmore for John

Cooper, including rebuild stern and cockpit floor, new Garboards, new deadwoods, planking, floors, frames, keel bolt, strip out old engine and replaced with Yanmar 12hp. Cork deck and varnish and paint throughout.

2000 - Shipped as deck cargo to Auckland, NZ.

2000 to date - Sailing Hauraki Gulf, racing in Classic Yacht Association Regatta. Ongoing maintenance including recorking decks, new headsails.

The Imogen today in New Zealand

In 1906 Otway, now in full manhood, attended the greatest event of the Irish Social year, the Dublin Horse Show. Held in early August, it was, and remains to this day, an international gathering which revelled in a week of racing and dancing, encouraged by the best food and drink the country could provide.

Muriel Bourne, the daughter of a stern English family, was the guest of a former school friend, in one of the many large house parties. Here Otway and Muriel, “paired” by a shrewd hostess, met and fell in love. Their romance was helped by glorious July evenings in lavish Edwardian hospitality. In the Ireland of that era, life for the fortunate was designed only for pleasure.

How different was the atmosphere of Muriel’s formidable home when she returned boasting of her romance.

“To an Irishman? My dear girl, you cannot be serious. Unreliable, like all Irish, and surely impecunious.”

No amount of explanation and re-assurance by Muriel could move the solid phalanx of opposition, and when two weeks later Otway arrived, dashing and impatient, to ask for Muriel’s hand, he was to feel the cold steel of Victorian England. The usual obstacles were raised: youth, money, temperament. When after desperate days of pleading, Otway received the dreaded ultimatum – a trial period of two years without contact – he left spilling Irish tears of mingled pain and anger, vowing that he would kill himself and that the Bournes could carry the blame with them to their graves.

With difficulty, a few letters passed between the lovers and in the following spring Muriel was sent on a world cruise accompanied by a dictatorial and socially conscious governess.

Otway, enraged and frustrated, certain that Muriel would meet scores of suitors on such a long voyage all of them eager to nurse her broken heart, nursed his own broken heart by falling in love with a daughter of a distant relative.

The thunder clouds gathered and in 1914 burst, shaking an established code as lightning strikes an old tree. Patriotism echoed round a world unable to comprehend its magnitude. To the far corners went a call to arms. The flower of manhood flocked to the colours, be it labelled friend or foe. By autumn of that fateful year Otway, proudly wearing khaki, was already on the Western Front, where massacre and slaughter would form a pyramid till Allied victory emerged four years later.

That same winter 'Tipperary' became an inspiration even in the grimmest trench, and with it came a telegram to Otway: "For your Christmas present have purchased Invernisk, Devotedly Muriel."

Otway had been born and brought up at Shannon Grove, the neighbouring estate to Invernisk, and his mother still lived there. As often happens there had long been a controlled rivalry between the two. Shannon Grove was older but Invernisk was a bigger house, built in splendidly proportioned terraces and beautifully laid-out gardens. His reaction was not happy. Why leave Cuba? What was this tactless "foreigner" doing to him?

The river, on which Otway had spent so much of his early life and in which his father had drowned, flowed gently through the grounds of both Invernisk and Shannon Grove, but all his life he had looked at Invernisk as a pompous mansion. How could he change his attitude now and what would be the reaction of his mother, whom he respected and loved, his outspoken sisters, all his senior, and those friends with whom he had sometimes scoffed at Invernisk Park. The incessant rattle of machine-gun fire, and the thudding of bursting shells made it impossible to feel any pleasure and excitement from the cable. True, Muriel, since their marriage about five years ago, had inherited a considerable fortune from an uncle. True too, that Cuba had only been rented. Originally Otway had intended to bring his bride to live in Shannon Grove, but at their very first meeting antagonism was apparent between his mother and his wife. One of these days he would try to get a short leave and surprise Muriel in her new home, without warning.

PEACE AT LAST, BUT NOT FOR LONG

In the early summer days of 1920, birds sang from dawn till dark and Ireland lived as it had always lived. Even the Great War, leaving a trail of destruction, misery and revolution across the face of Europe had made no mark, as yet, on its most westerly isle.

To this quiet backwater, Otway Waller returned unscathed from five years of war. His early love of motorcars, dating from the purchase of a Panhard in 1902, had earned him an unexpectedly early exit from the trenches on the Western Front in 1917, on being appointed a member of General Allenby’s Mechanical Transport Corps in Palestine. There in the hot sunshine of the Levant, he enjoyed the following two years, visiting Jerusalem and Cairo with regularity.

Muriel, buying Invernisk as a grass widow shortly after the outbreak of war, became accustomed to holding the reins in her own hands. Certainly there were those brief leaves when Otway burst in on the tranquil life of Invernisk: no more than a visitor, and nervously excited with his curiosity overflowing in many directions, he had brought colour to her new home; but always there had been the grandfather clock in the hall chiming out the limits of his freedom.

The rearrangement of their lives was not easy, nor would it pass without friction and a certain unhappiness. Otway, strong and healthy, had used his ‘local’ leaves for amusement and had enjoyed, to the full, the nightlife provided by an endless variety of mixed-blooded hosts and hostesses. The hosts had shown an effusive welcome to the noble soldiers, and the hostesses had quickly taken over after the first few shallow greetings. Thus it has often been, that the simple fidelities of home become clouded through time and distance.

Muriel, the protected flower of a stiff and not always happy childhood and adolescence, had learned from Otway all she knew of sex. In their life together before the War, a pattern was woven, and even the long years between had not dimmed her memory. With Otway’s return, it was obvious to her that this pattern was now changed. Repelled at times, she had fought hard enough to hide her feelings and Otway, hurt and rebuffed by this new coldness, missed the mechanical, if mercenary, reactions showered on him in the East. Their daily life was different also. Otway’s wild enthusiasm for his own interests was no longer shared by Muriel. At golf, he became expert as she became more nervous. In sailing and fishing, his impatience increased till she became stubbornly disinterested.

On the morning of the fourth day, a fresh breeze was blowing from the southwest as Peter came out early on the deck. For this day, he had waited with excitement for it contained the race for the prized Raheen Silver Cup, and his father had promised that he should be in his boat. The race was for centreboards, the name given to the popular sailing boats, which instead of a fixed keel possessed a movable centreboard made of lead. Fast and quickly manoeuverable, these boats had been the pride of various yacht clubs situated up and down the River Shannon. Since it was possible to lift the keel almost completely out of the water into a wooden compartment in the centre of the boat, they travelled more quickly through the water, but in squally weather there was a greater danger of capsizing, unless the centreboard was quickly and adequately lowered.

* * * * * *

One day, Martin had rowed across and asked if he could borrow Con for a while to help him take a drum of petrol from the jetty to the Rosanagh. Neither of the men asked Peter to accompany them. Together they rowed away leaving him crestfallen at the Christina’s stern. His father and mother were sailing and Dannie was busy in the engine room. From his cabin, Peter fetched the small telescope he had been given on his ninth birthday. Back on deck, it was easy to watch the progress of the two men. For a while they rowed towards the Raheen jetty, then they veered away to the right and headed down the bay. As the distance grew, Peter’s curiosity increased. So little of his life had contained suspicion, and now here were his two friends living a blatant lie right in front of his eyes. In the wheel house hung his father’s powerful binoculars, more useful now than the telescope, and with these he could see the boat heading for a clump of thick rushes. His youthful mind was now playing detective, and soon he discovered that other rowing boats were already hidden in the rushes. Soon all movement ceased and the boats lay concealed from both the nearby shore and Raheen’s busy jetty. Peter’s curiosity was now at fever pitch and he ached to hear the conversation that must be taking place. One thing did not escape his notice: the day and the time had been well chosen. At the moment all attention was centred on that day’s sailing race. Owners of yachts were far out on the lake, and all eyes at the Club House were following them.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE BLACK AND TANS

In the weeks of Peter's absence, Con had changed more than he dared to realise. Each day, during the long summer of 1920, had strengthened the bands of resistance against the bondage of suppression. Centuries of an unaccepted overlordship were being rolled back by the diehards and fanatics, and in their wake came Con; for Con was ensnared in the "Fight for Freedom", so soon to echo round the world of those that cared and to be written off by the rest in a masterpiece of understatement as "the troubles". Con had been recruited by Martin McCarthy.

* * * * *

As Con’s match flickered to life, he counted three silhouettes in the confused lights of the moon, car headlights and a thick yellow haze from the staircase. He threw it into the bundle of straw, only a few feet from where he stood. A blinding burst of flame lit the empty room and sped down the path created from his petrol can. Instinctively, he followed his instructions, numb even to the shouting voices which had not been part of his briefing. As a rat from a burning haystack, he fled through the open door. In the clear night air, shots sounded only yards away, and a groan nearby made his blood run cold.

* * * * *

Those with revolvers in their belts fired to left and right. It was an ambush indeed. Blazing acetylene headlights lit up the foreground, but on either side of the road lay darkness and enmity. As men fired their bullets into that darkness, the first truck slowly pushed aside the hastily erected barrage.

“Back men, let’s go!” called a husky voice and in the partial silence that followed only two further shots were fired at the stark ruin of the barracks. From behind the wall came a piercing cry. Martin, knowing victory was his, had stood up to watch the shambles of his enemy slink away in defeat. It was this last bullet which entered his body – another night’s work had taken its toll.

On the long journey home, Otway and Margaret would make the most of their early morning meetings. He told her how everyone in Ireland rode horses and hunting was done by other than just the gentry. She told him that she had had a pony when she was three years old that carried her to school. At ten she had been presented with the mask of the fox at a hunt at Chartwell in Surrey.

He sat as her patient model, when she sketched him. She began to get deeper into his past life and he told her that his marriage was on the rocks.

Otway realised that he had found a companion who would love his sport. She was by now deeply in love. There were too many spinsters after the Great War and too few men of her age alive. There were younger ones that had missed the war. But here was a real man, who was very strong and very gentle. Their last night on board sealed their future.

Next morning, as the Aguila was sailing up the Mersey, Otway took Margaret into the ship’s three-foot-square library.

“Margaret, I am going to marry you!” he said.

“Otway, catch me if you can!” she replied.

CATCH ME IF YOU CAN!

The future of their whirlwind romance now depended on Albert’s view of the adventurous Irishman. The two men returned to Albert’s study. Albert liked the Irish – they were great workers on the houses he built – but he wanted to know more about Otway’s family back in Ireland.

“My grandfather William Thomas married Elisa Guinness, a granddaughter of Arthur Guinness, the founder of the brewing family. His eldest son, George Arthur, joined Arthur Guinness Ltd after leaving Trinity College, Dublin, and became the Chief Engineer and Chief Brewer. Uncle Edmund ran the horse transport department, transporting the Guinness around the country. My father, Francis Albert, was a barley buyer and set up F. A. Waller Ltd, the Maltings in Banagher in Offaly, to provide the malt for the brewery. Uncle Robert did the same at Nenagh in Tipperary.”

“And as Guinness is very popular, and I am sure profitable, the family has money?”

“It was once said that every drop of Guinness drunk in Ireland had passed through a Waller’s hand.”

“So you could look after Margaret in the way she has been accustomed?”

“Of course, I am the Managing Director of F. A. Waller and also the chief chemist.”

“That sounds perfect. I’ve heard of the Irish gentry marrying Englishwomen for their money. Let me tell you, Otway, if you ever had a penny from me, it would be a loan and I would charge a commercial interest rate.”

In Banagher, the Maltings were running steadily. On her visits, Margaret was popular with his many sporting friends. She could ride a horse over the fences as well as the Irish. She learnt to shoot and fish, and she was a vivacious addition to the gatherings of his friends and family.

In London, they had a car that she drove to visit her family in Kent and Surrey. Everything was fun; including the time that Otway chose to go through Marble Arch rather than round it to avoid other cars. He used all his Blarney in a broad Irish brogue to explain to a bewildered policeman who had stopped them that he was completely ignorant of the confusing traffic in London, as in Ireland there were no cars on the roads at all.

In June tragedy struck. The Offaly Chronicle, 25th June 1931, reported that:

In the early hours of Thursday morning, 18th inst., “Inverisk”, the beautiful mansion of Capt. Otway Waller, was almost completely destroyed by fire.

* * * * *

On September 5th 1931, Margaret became Mrs. Waller at Kensington Registry Office. They left immediately for Banagher, to their home on the Shannon. The Wayfarer was 64ft long with a Thames Measurement of 43 tons. On the stern were two parallel rails onto which a car could be driven and parked. Inside everything was mahogany and quilt; a romantic abode for a new bride.

“Are you going to carry me over the threshold?” asked Margaret.

“Of course,” Otway grinned and then searched for the keys to the Wayfarer. “Oh my God, I’ve mislaid the keys.”

“So what do we do?”

“I’m afraid you are going to go in through a porthole and then open the door from the inside.”

In she went, head first, into the “heads”. So started an exciting life for the newly-weds.

* * * * *

The battle then sank to a lower depth. A leaflet ‘A Warning to Potato Growers’ started to circulate throughout the country. The organization behind the distribution of the leaflet has never been proven, but Margaret heard that in their sermons the Catholic priests damned the ‘Devil’s Poison’ sold by a divorced man.

In December 1933, Otway, resigned from the family firm and set up Farm Requisites Co. to sell Bouisol and Ceresan.

On January 28th, 1935, with Margaret six months pregnant with their first child, Otway sold Farm Requisites to Horace Hammond, Wholesale Product Agent and Importer, of Dublin. He had decided to move to England.

On May 27th, 1940, the evacuation of Dunkirk started. What would be next? Hitler was making ready to invade England, perhaps over the shallow beaches of Romney Marsh. In the summer and autumn the brave young pilots fought the Germans in the skies above Hythe and East Kent.

Otway and Margaret discussed their dilemma: they had enormous financial problems and their family was in danger. Otway declared himself a war bankrupt and they decided to evacuate as well. In May 1940, they set off for Perranporth in Cornwall, where Otway had obtained a job as a coastguard. To the young family there was an addition, newly born John.

They parked the caravan at Gears Sands, just above the closed golf course. Otway had a couple of golf clubs and a few balls. The wheels of the car were removed and it was put up on blocks for the duration of the war. He erected a chicken hut in which he spent many nights, as he had to leave at odd hours to go on his ancient BSA motorbike and sidecar to the coastguard station.

If life appeared carefree for the children, their parents faced problems. The £3 a week Otway earned as a coastguard could have easily paid the house expenses, but it wouldn’t also pay for the bottles of whiskey he had grown used to in his life in Ireland. One day at work, perched high above the sea, he noticed a barrel being driven through the surf. He jumped on his motorbike and rushed down to the beach. He pulled it ashore and unplugged the bung. It was truly treasure, neat industrial alcohol. As a chemist and with his knowledge of poteen he knew the liquid could be dangerous. He offered the first drink to a soldier, who didn’t fall over, so he strapped the barrel onto the motorbike and delivered it to his chicken hut.

Both Otway and Margaret were fiery characters and the fights in the caravan were traumatic, particularly for Jimmy. Saucepans would be thrown and then Otway was sent off to the chicken hut.

In 1949, Otway took the family back to Carrick-on-Suir. The highlight of the summer was a golf match at Clonmel between John Burke, Joe Carr, Jimmy Carroll and James Bruen. Otway was bringing up his boys to follow in his sporting footsteps. They also drove up through Limerick and were shown the Shannon Scheme, the Ardnacrusha hydroelectric power plant, one of the wonders of Irish engineering, built by the German giant Siemens with many German workers.

Back in Folkestone, every daylight hour was spent on the golf course, either playing or looking for balls in the Pent Stream that passed through eleven of the eighteen holes. These were sold to make up for the pocket money the boys did not receive.

* * * * *

On February 14th 1950, with the winter weather holding off, they drove over to Littlestone for their picnic and golf. Margaret sat in the front of the car and Otway was in the back eating his ham sandwich.

“Margaret, I am so happy. It’s the first day of spring and we are out on the course again. Be a dear and pass me the mustard.”

She turned round to hand it to him. He was dead.

Heavily indebted and unable to sell any flats because of probate, Margaret went into the East Kent mining villages to sell Encyclopaedia Britannica. Any commission she made not needed for housekeeping went to buy shares, such as Marks and Spencers and Marley Tiles.

* * * * *

Margaret played golf to a high standard and was a leading portrait artist in the Folkestone School. In 1989, aged 90, she attended a small reception at the Royal Cinque Ports Golf Club, Deal. She presented one of her portraits to a member.

"Margaret, please would you sign the visitor's book," requested Nigel, the secretary. Margaret obliged.

"And put your date of birth." She added 3.6.1899.

Nigel pointed to a visitor who was born in 1889.

"Nigel, give me the book." She added: "and still playing golf."

She died in 1993, aged 94.

APPENDIX 4 - A LETTER FROM AFGHANISTAN 1842

The following letter was written, during the Retreat from Kabul in 1842, by my ancestor Captain Robert Waller, Bengal Horse Artillery, to his parents after he had been taken hostage. It was printed in the Irish Times. Of 16,700 who left Kabul only one – Dr. Brydon – reached Jalalabad. Captain Waller was later released.

* * * * *

A few days from the commencement of the retreat completed the destruction of the force – it was a dreadful time as we passed along over the dead and dying, the wounded and frostbitten of our comrades and friends. No questions were asked, no assistance to the wounded could be afforded, where they fell there they lay to be butchered in our sight by our enemy who spared none except a very few who happened to fall into the hands of the chief men – among who were myself, wife and child – I was severely wounded in the action previous to the retreat and have a bullet in my right side now which passed through my arm below the shoulder and before that I had been wounded in the head, but not severely.

Akbar Khan has treated us with much more kindness and consideration than we had reason to expect under all circumstances. He supplied our wants to the best of his ability for we saved not an article or sixpence, having escaped but with the clothes on our backs, and for more than a fortnight we had nothing but these, day or night in the middle of winter, and having been on the bare ground or on the snow. Negotiations for our release have been tried, but without success as yet. I believe, however, that Akbar is willing to make terms if they are not too hard upon him. He has promised to forward this letter for us, and I am going to send it open.”

APPENDIX 5 - EXTRACTS FROM THE COURT CASE

“There were peculiar circumstances in connection with the burning.”

Midland Tribune, 17th October 1931

At Galway Circuit Court, on Friday (before Judge Wyse Power) Capt. Otway Waller claimed compensation for the alleged malicious burning of Invernisk House, Banagher.

Several witnesses were examined, and the further hearing adjourned to Saturday, and the Judge gave his decision that evening awarding the applicant a total decree for the house and contents of £5,789 4s 6d, with cost and expenses, when taxed to be levied two-thirds as a county-at-large charge on Galway, and one-third as a county-at-large charge on Offaly.

APPENDIX 6 - A SOLUTION TO POTATO BLIGHT

On September 13th 1845, there was another dramatic paragraph in The Gardeners’ Chronicle: “We stop the Press, with very great regret, to announce that the Potato Murrain has unequivocally declared itself in Ireland; for where will Ireland be, in the event of a universal potato rot.”

* * * * *

[In 1892] the technology of it was simple enough – so far as the farmers were concerned – but success depended upon using properly made mixture and applying at the right time.

One way of diffusing the necessary information was by means of printed leaflets. But a great many of the farmers in England and in Ireland – though not in Scotland – were illiterate. In time, with the help of the priests in the pulpit and the teachers in the schools, the message that there were advantages of using Burgandy Mixture very slowly became apparent to the farmers.

* * * * *

The product was put on the market with tentative recommendations for use in 1931 under the trade name of “Bouisol”. This refined colloidal preparation proved its worth; it won an established place among the really scientific chemical therapeutants for use on plants.

* * * * *

With Bouisol, one of the disadvantages of the traditional Bordeaux and Burgundy mixtures was at once overcome: the requisite quantity of liquid had merely to be run out of the barrel and poured into the water in the spraying machine; all the labour and delay involved in preparing copper mixtures on the farm was eliminated.

website designed and maintained

by Hereford Web Design