Irish Flames

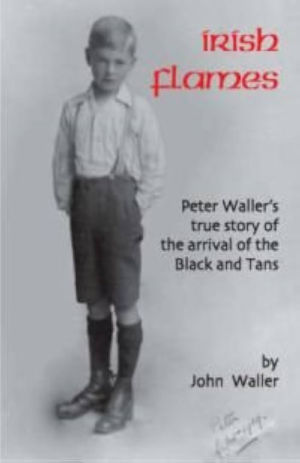

Before Peter Waller, co-founder of the American School in London, died in 1990 - he is pictured below aged eight - he gave a partial manuscript to the author, his half-brother. Here is his story.

Irish Flames is a thriller. It is based on Peter's memories of his childhood and the 1920 arrival of the Black and Tans. It is set in heart-wrenching times, intertwining flames of freedom, flames of hate and flames of love,

The white of peace links the Green and the Orange in the tricolour, the flag of free Ireland. Irish Flames brings together, in tender affection, the Green and the Orange in the War of Independence. They unite against the barbaric Black and Tans, brought over by the British to "beat the hell out of the Irish".

"If the persons approaching (a patrol) carry their hands in their pockets, or are in any way suspicious looking, shoot them down. Innocent persons may be shot, but that cannot be helped. I assure you no policeman will get into any trouble for shooting any man."

(Englishman Lt. Col. Smythe, June 1920)

"Very good read. Most enjoyable."

Dr Rory Masterson, Offaly Historical Society

"A riveting story told with pace. Compelling and visual."

Lucy O'Sullivan, Midsummer Films

"It is bound to strike a chord with a great number of readers."

Christina Sloan MBE, Librarian, Armagh

AUTHOR'S NOTE

My father was an Irishman; so why am I English?

On Saturday June 14 1930, he stayed with his friend, Conor O’Brien, in Foynes, Co. Limerick. Next morning he set sail, along the circumnavigation route taken seven years before by Conor in his yacht Saoirse (Freedom), in his own epic single-handed cruise to the Canary Islands in his 26ft yawl. Returning home on the Yeoward Line s/s Aguila, he fell in love – with my mother.

Back in Ireland he had a problem: he was already married with a son, Peter.

Recently I decided it was time to re-discover my roots. I went back with a sense of guilt. In the 1920s he won a medal in the Tailteann Games, the ‘Irish Reconciliation Olympics’, had been almost unbeatable as a yachtsman on Lough Derg and had been a scratch golfer at Birr and Portmarnock – he was a real Irish sportsman. But his English wife had been so different – she loved her books and her garden.

I then found a family ‘secret’. I no longer felt guilty. Details were impossible to come by until I searched through the shopping bags of family papers, letters and photos my brother Peter had given to me before his death in 1990. I found he had written his childhood story. It told of the War of Independence, the arrival of the Black and Tans and details of the ‘secret’.

During my research, I have traced the people and places in the story. In respect for the past and the sensitivity of the present, I have changed their names.

INDEX

The way is blocked

Black and Tans

The Volunteers

Dublin in 1920

Homecoming

Flames of freedom

A summer's dawn

A casualty is found

Flames of love

Unwelcome guests

Ambush

Flames of hate

Peter Waller

Alec Casemond, built like a bull, short and square, now in his mid-thirties and matured from four years in the War, drove carefully.

He had already crossed, with difficulty, a damaged bridge. One side wall, blown away by a mine, revealed below in a swirling river, an almost submerged army lorry. There remained of the bridge barely enough for a donkey cart to pass over. Slowly and in silence he manoeuvred the car across what seemed an interminable distance. His wife Meli had been free to walk, but eight-year-old Robin, lying helplessly on the back seat, with a broken leg, could but trust in him. Alec’s relief in successfully negotiating this gruesome reminder of his country’s plight gave him new energy and courage.

In that early summer of 1920 the political storm clouds had gathered around Ireland. The dream of Independence, for which the blood of seven centuries had so often flowed, appeared as elusive and remote as ever. Promises, half promises and innuendoes evaporated, leaving first disillusionment, then bitterness and now open and active hostility.

During the spring of 1920 a crowning insult had been inflicted upon a harassed and poverty-stricken Ireland, when English jails provided ‘soldiers’ considered suitable to deal with the Irish question. These misfits of society were of a low mentality and largely unemployable and dangerous. What an ironic solution it was to give them a free hand in Ireland, thus relieving the pressure on the overburdened British prisons.

Training was unnecessary, since discipline was neither expected nor required. Not even the tradition of a conventional uniform was important. In their thousands they came, a motley crew of murderers, the ‘Black and Tans’, some wearing black trousers and tan jackets, others khaki trousers and black jackets. They looked, and indeed many proved to be, material for the hangman’s noose.

In silence, the three men trudged into the slime and put their shoulders to the back of the car. Up to their ankles they pushed, but to no avail. The tall man removed his shabby coat and placed it under the back wheels. He smiled: ‘It’s for the little lad,’ he muttered shyly.

‘God bless you,’ Alec replied. He let in the clutch very gently and, helped by a mighty shove, the car floated on to the grass. Ahead, the cart track was firmer; some gravel had recently been thrown upon it. As the car gathered speed, he saw ahead the open gate leading back to the road. He dared not stop for fear of getting bogged once more, but once out on the road he pulled up and jumped from the car to give his thanks. No one was to be seen and all was silent. They had gone as silently as they had come, those mysterious but kindly men. God grant them safety from unfriendly bullets, was Alec’s heartfelt wish.

Dublin – Fair Maid of Ireland – sat astride the River Liffey, whose waters, gleaming and fresh within a mile or two of the City, became changed to a dubious hue as they passed under its many fine bridges.

Pride of Georgian architects and home of the eighteenth- century elite, its beautifully proportioned houses, with their fan-lighted entrances, now in whole areas housed hordes of penniless and hungry rabble. The carved front doors had long since during cold, wet winters, been chopped up for firewood; and on the marble steps, once scoured white, sat groups of black-shawled women, their ragged children – urchins indeed – playing or fighting upon the pavements.

The main thoroughfares were crowded, indeed over-full to be healthy or so it appeared to those who knew Dublin in former years. At every street corner stood groups of men, their dark and shabby clothes not speaking of prosperity nor even showing marks of physical toil. Since the end of the Great War, times had been ever harder for the great numbers of men released from war service. In those days, home industry was almost negligible and, for centuries, the industrial needs of Ireland had been provided by an England across the sea.

At the foot of the grey stone steps, Con O’Toole, tall, thin and worn, though only twenty-three, removed his cap. His eyes burned with happiness; for life – his life – had returned to Merlin. As his master stepped from the car, out tumbled also Robin, the little boy who had meant so much to him in recent years.

In the weeks of Robin’s absence, Con, the simple youth, a tenant of great Merlin, had changed more than he dared to realise. Each day, during the long summer of 1920, had strengthened the bands of resistance against the bondage of suppression. Centuries of an unaccepted overlordship were being rolled back by the diehards and fanatics, and in their wake came Con; for Con was ensnared in the ‘Fight for Freedom’, so soon to echo round the world of those that cared and to be written off by the rest in a masterpiece of understatement as ‘the troubles’. Con had been recruited by Martin McCarthy.

Con’s hands shook as he held the match box which was to ignite his own tinder box. Only one flight of stairs separated him from his mates and the deathly flames. Three quick thuds on the ceiling above his head were mingled with the roar of a motor car. Headlights shone brilliantly through the broken window where Con stood. Time stopped. The match shook as he tried to strike it. Now all was confusion. Boots clattered down the single flight of stairs followed by gusts of rancid smoke, burning straw, petrol and old timber. Outside voices were raised in querulous demand. As Con’s match flickered to life, he counted three silhouettes in the confused lights of the moon, car headlights and a thick yellow haze from the staircase. He threw it into the bundle of straw, only a few feet from where he stood. A blinding burst of flame lit the empty room and sped down the path created from his petrol can. Instinctively, he followed his instructions, numb even to the shouting voices which had not been part of his briefing. As a rat from a burning haystack, he fled through the open door. In the clear night air, shots sounded only yards away, and a groan nearby made his blood run cold.

‘Lads, run for your lives, live to fight again!’ The words were Martin’s and as they ended they were followed by the voice of Colonel Kernahan, Squire of Ardmore Castle.

‘Rats, bastards! We’ll get the lot of you!’

During the early summer, Merlin knew almost no night. The pale dawn cast its ethereal but dead whiteness over the sleeping fields. A wren – brave little bird – gave her solo notes. At first, the earth still slept, but she had disturbed the conscience of a blackbird, whose little clearing of the throat allowed her to announce the new day. In its turn, the rest of the bird world closed its ranks and then, as Robin listened from his window, the crescendo glory of the morning chorus filled Merlin’s park. Tireless, the cuckoo, who had repeated his beloved call till late into last night, was once again telling of his happiness to be here in the greenness of this tranquil island, far from his southern home. More than one pheasant gave notice of its whereabouts – tame birds, reared by motherly Merlin hens, one day they would rise on the autumn breeze and meet their end through man’s lust to destroy.

The song thrush and robin now, from their different trees, vied with each other to lift their song into the golden rays, heralding the coming of the sun. Across the fields the river, a great grey snake, lay still and from its rushes came one by one the calls of coot, grebe and waterhen. Nearer, a plover raised his worried call above the meadows and from the marshy ground came that of the haunting curlew.

‘Con, dear Con, what’s wrong? I have looked for you everywhere. I’ve been up since 4 o’clock and I’ve been to Firgrove Wood and, Con, I’ve got to talk to you, it’s so important.’

As Con looked up, Robin saw how white his cheeks were and he looked into the dark sunken eyes.

‘Shure Master Robbie, I’m feeling terrible weak this mornin’. Didn’t I have a bad spell of coughin’.’ Con had to think and lie quickly, for this small boy must know nothing of his night’s ordeal. In a way he wished he could tell him, for it would relieve his troubled mind. But rules were rules and he had been warned against giving away any information, and if he were to do so to a child, his fellow rebels – for he was one of them since last night’s work – would show him no mercy.

Robin’s next outburst nearly caused him to stop breathing.

‘Con, I had to find you. Something terrible has happened.’ Without pausing, the boy ran on: ‘Up in the wood, you know where there’s the old cavern, Scram and I found a wounded man. He says he has no name, but he is shivering on a pile of straw, which wasn’t there the last time I went; and he has blood on his clothes. I told him that I would get him food and a blanket. Oh Con! He is so cold and sad in there. I think he’s frightened there alone and he told me his leg was broken – you know like mine was.’

The Irish Mail, bound from Holyhead, that quaint fingernail of Welsh soil, rattled its journey over the sleeping miles towards London. Meli, alone save for a carriage companion, allowed her mind to float across the last few years of her marriage.

She realised that, originally, the Irish Sea – indeed each of its seventy-four miles – had been a gulf that her love and infatuation for Alec had bridged quite simply. The guns of Flanders were not audible in Tipperary, although a million khakied men had ploughed through muck and torment to the tune of the same name.

The rhythmic click of the carriage wheels beat out the strain once more.

Why then had their life together changed so much? Could the fault be hers? Here on English soil, she could ponder anew. To her, Alec had become so self-contained. A true sportsman, he lived for the interests that dominated every Alec through the centuries.

Yet, enmeshed from birth in the custom of her class, there had come to burn in Meli’s heart a flame of a different hue.

From behind them came the music of a small but efficient local band. Alec’s smoking room had, for the evening, become a well-stocked bar and, as the cars continued to arrive, soon became crammed and noisy. But this was New Year’s Eve when the world was celebrating and who knew better than the Irish how to celebrate.

In the distance, beyond the front gate, a bright light shone and this was soon joined by the roar of motor engines. As they drew nearer, a cold shiver went down the backs of both Meli and Alec. On the lonely roads of Ireland in the winter of 1920, that particular roar meant one thing: the Military, and more likely still the dreaded Black and Tans. As the lorries turned in at the main gate, Mary O’Toole felt the same shiver creep down her spine. This could not bode well for Merlin or its guests, for no one, no true Irishman, invited the Black and Tans inside their doors. To do so might bring disaster in reprisal.

Con gave one of his rare, shy and apologetic laughs. ‘For shure ’tis deep out of the ground they came and isn’t that where they belong anyhow?’

The words were hardly finished before the distant roar of engines pierced the quiet winter’s night. Martin’s men needed no instructions. Without further word, Con slid back into the laurels. He and three others pulled out from the darkness heavy wooden beams taken from the ruined barracks. Martin’s boys lifted lumps of fallen masonry over the wall and set them across the road. Within sixty seconds, they had set an ambush through which no car would try to pass. Back in their positions, they watched the brightening glare in the sky.

‘This is it boys,’ called Martin. ‘Our chance has come. Long live Ireland! Up the I.R.A!’ Weapons of death waited on both sides of that little unpaved road, where humble donkeys had carried their loads since the beginning of time.

The first lorry’s driver, surprised at what appeared through his windscreen, pulled hard on his hand brake. He had drunk more wine than some of his fellow men. What was this unexpected obstacle in the road? The men behind him in the open lorry lurched forward and continued to sing ‘Bonnie Scotland’. Major MacTaggart, satisfied with his night’s success, had dozed off. ‘What the hell!’ He never spoke another word. From both sides of the road a cascade of bullets showered into the leading truck. The major slouched back, a thin stream of blood flowing from his right temple.

As he stood by the shed, he could hear voices, men’s voices, coming across the still night air. They came from Merlin. Maybe the Master had visitors, but why the shouting? He was tired now. If only Master Robbie would return, he could lie down and sleep on the damp shed floor, for tomorrow he must leave and hide himself somewhere. He knew not where, but now, he reminded himself, he too was ‘on the run’.

As the shouting continued, Con saw, as in a dream, a light from the big house. At first it flickered, and then took hold. Now, as he watched, it grew into a brighter light, engulfing the hall. Then he heard the grinding of an engine, and the roar of a lorry – the Black and Tans, Con knew, had struck again. Through the winter, they had burned houses where they suspected opposition to their authority. But why Merlin? How could they know that Martin had lain hidden there from their fury? Suddenly his heart went cold. Whatever the reason for their action, he knew that little Robbie had, for his sake alone, gone to the house, now belching flames, to fetch food and blankets. He could not stand here and watch Merlin burn before his eyes, with the boy trapped inside it.

Peter Waller, John’s half-brother, was born in Ireland in 1911. He worked in the American Red Cross in World War II, as house manager at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, as salesman of vast Crown Derby dinner sets to the sheikhs and kings in the Middle East and as joint founder of the American School in London.

He was a friend of Gerald Durrell, author of "My Family and Other Animals", and organiser of his US fund-raising tour. In retirement he spent much of the year in Corfu, appearing as a major character in "Greek Walls". He died in 1990.

website designed and maintained

by Hereford Web Design